John Boyd: "Machines don't fight wars."

|

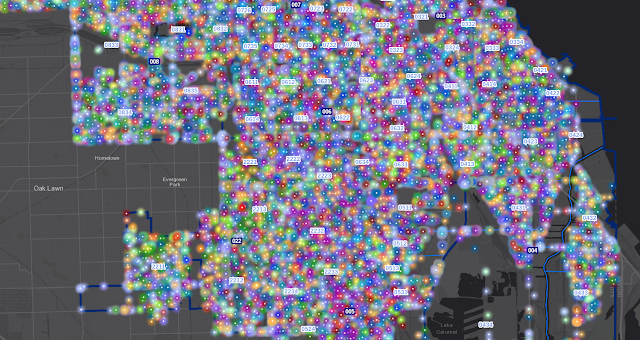

| Chicago Police Crime Map (City of Chicago dashboard) |

“Machines don’t fight wars. Terrain doesn’t fight wars. Humans fight wars. You must get into the minds of humans. That’s where the battles are won.”

~ COL John Boyd, US Air Force

I'm a vocal supporter of data, technology, and intelligence in policing.

- Data is the collective of facts, clues, timestamps, map points, and evidence used to develop intelligence.

- Technology is the aggregation of tools, methods, and mediums by which data is sensed, captured, sorted, stored, analyzed, correlated, transmitted, curated, and shared.

- Intelligence is the resultant storytelling product and team sense-making of threats, crimes, investigations, and evidence, ultimately used to inform decision-makers.

NONE of this happens without the integration of humans.

I don't care how good your artificial intelligence is. Or your algorithm. Or how timely or accurate your automated alerts are.

Effective policing and public safety require a human touch.

Right now, there's a huge movement in US policing on Real Time Crime Centers or RTCC - where sensors, alerts, videos, and other information is immediately available to or shared with first responders in the field. In the last few years, it's become somewhat of a cottage industry. The competition between tech vendors is cut-throat. And when you factor in tech companies acquiring tech companies, the allegiances and alliances shift quickly!

Whether you're talking about:

- AI that detects objects/people/guns in video streams;

- cameras that detect car license plate characters;

- audio systems that detect gunshots in the community;

- GPS geo-fence alerts;

- integrator dashboards that bring technologies together...

Each of these force-multiplier products strive to tout themselves as being faster, more reliable, more universal, and more accurate than their competitors. Basically, it's turned into a game of how fast a vendor can routinely put the most accurate information, from the widest variety of data sources, into the hands of those doing the job.

It's turned into a game of how fast a vendor can routinely put the most accurate information into the hands of those doing the job, from the widest variety of data sources.

What's often glossed over is that every single one of these technologies requires human involvement, discernment, confirmation, opinion, or discretion.

Every. Single. One.

That's not to say these technologies aren't useful. They're actually ridiculously useful. And the most useful ones are those that require the least amount of human involvement. But some claims are exaggerated on how well these technologies work by themselves -- without people.

And people are expensive!

I will not discuss specific products. First off, I have exactly zero personal stake in any of them -- financial or other. Nobody is getting free endorsements today. Secondly, this is an arena where I believe public transparency should not be full. Some tools used by law enforcement and security industries are effective simply because people don't know about them. Lastly, I'm not the guy (and my Department is not the sort of department) who has to brag about all the capabilities we use to do our job.

I've been fortunate to work with, be exposed to, or at least be familiar with most of these above technologies; I use a fair amount of them weekly or daily, if not hourly.

Here are some lessons I've learned:

Every single one of these technologies has failed and has vulnerabilities. Have you seen the story about the Marines sneaking up on an AI camera while inside a cardboard box? Anyone who's worked with license plate cameras knows what factors go into poor captures or faulty recognition. The false positives need to be weeded out. I've seen humans turn off alerts because of such low accuracy rates, the systems were "boys who cried wolf" and the noise was simply distracting to their operations.

We must acknowledge the false negatives as a vulnerability -- where some legit threat sneaks in undetected. You'll never catch 100% of the threats; claiming to do so is disingenuous. (I mean... if you haven't thought about how you might be able to fool gun/weapon detection AI, you're not really thinking ahead here.)

Likewise, claims that [Technology X] would have resulted in [Result X] is just as asinine. If the situation and technology is something can be tested post-event, I always suggest that the technology be tested by a neutral third-party with transparent results posted within the industry. If you want to tout your tool, put it out there! The game of make-believe is a bad look.

Most of these technologies can be used nefariously. There's always one weird story per year where some hot-headed copper monitored his ex-wife's car license plate in some confidential database. Frankly, every system I'm aware of maintains strict audit logs of activity and queries. Secure credentialing and multi-factor authentication is the norm for almost all of these platforms. Progressive agencies run random spot checks on their members' activities.

These technologies need staffing. Maybe not people sitting at 24-hour desks (but maybe). But they do need humans to verify any and all alerts before taking enforcement action -- especially those that lead to a search and/or a seizure. (Though you can start smartly mobilizing resources before such a verification.) Experience with these technologies is important; verification frequently relies on analyzing nuances and subtleties that inexperienced operators miss. Even at that, diverse operator teams bring in divergent mindsets that can verify or reject alerts better than any solo operator.

The Swiss Cheese Model of failures. Each of these technologies is a slice of Swiss cheese, rife with holes. Some technologies with bigger holes than others. The trick is to figure out how to close up the holes, stagger the holes, or otherwise filter out the mistakes, errors, or vulnerabilities. One way is to add slices of Swiss cheese by way of new technologies and smart humans. This must be a full systems approach, with multiple layers, each overseen by people.

This must be a full systems approach, with multiple layers, each overseen by people.

It's easy to fall for Shiny Objects. The technology is advancing so quickly, it's difficult to keep up. It seems like there's a new tool every month. (And every time I post on LinkedIn about RTCCs or intelligence-led policing, it must be received as a public invitation to all tech vendors to hit me up in private messages to sell their product!) Not all of these technologies are equal; some are simply more foundational, more widely useful than others; others are more niche. Your agency must prioritize its budget, its focus, and what it can consume. (Dare I suggest you use intelligence to help determine these priorities?)

That being said, there is a certain collection of technologies and capabilities that should be required for any police agency to consider itself contemporary. With 18,000 agencies in the US, we aren't anywhere close to having modern policing nationwide. For many areas, regionalization of these efforts is the best option -- where the technology costs are shared, as are the costs associated with any specialized staff.

This latticework of technology goes way beyond the world of RTCCs(which tends to be a fast-paced, tactical-intervention game) and into the related field of intelligence. Intelligence is where we discover and explain patterns, trends, and predictions. It too requires humans -- arguably more so in intelligence than in the RTCC realm. For the foreseeable future, intelligence will remain less automated, more complex, more strategic, and require a more artful skillset. As such, human judgement, opinion, and critical thinking will continue to be showcased in intelligence functions.

For the foreseeable future, intelligence will remain less automated, more complex, more strategic, and require a more artful skillset.

To summarize:

Whether in real-time support or in longer-term strategic intelligence, we need good people who understand the expanding latticework of technologies and how they intersect, overlap, and connect. We must be the drivers of these technologies - so that they are answering appropriate questions and looking for the right things. Thoughtful intelligence should feed-back, so that it further informs strategies and technologies. Despite what I've seen in some places, people must remain in control.

As imperfect as humans are, they'll always be required to "check-the-work" of these algorithms and machines that are enhancing our capabilities at handling the exponentially growing field of data coming out way.

Invest in people. In their minds is where the battles are won.

***

Lou Hayes, Jr. is a detective supervisor in a suburban Chicago police department. He's focused on multi-jurisdictional crime patterns & intelligence, through organic working groups compromised of investigators & analysts from a variety of agencies. With a passion for training, he studies human performance, decision-making, creativity, emotional intelligence, & adaptability. In 2021, he went back to college (remotely!), in hopes to finally finish his undergrad degree from the University of Illinois - Gies College of Business. Follow Lou on LinkedIn, & also the LinkedIn page for The Illinois Model. ***

Comments

Post a Comment