Police Use of Force Continuums Are Broken (But So Is The Case Law Approach)

Back in 1998, in the Police Academy, I was taught a Use of Force continuum.

Pay no attention to the fact that my Police Department's main directive on Use of Force (drafted 1995) was a case law-based policy.

What I've come to understand over the last two (2) decades is that neither is a suitable model, guide, or training tool to help street cops make the best decisions. What I'm advocating here is a hybrid approach that will inevitably piss off both camps. That's often the price of compromise...

***

Let me start with this: Police Use of Force (UoF) can NOT be quantified, measured, mechanically-applied, or accurately categorized by statistics.

Take simple incident reporting as a case-in-point. The best we can do is to create an arbitrary standard that turns police action into a reportable UoF incident. How many UoF incidents did a police department have in the last year? Count up the UoF reports. Hint: It'll be a whole integer.

However, what benchmark turns a gentle hand-on-the-back re-direction around a hallway corner into a reportable UoF? How much struggling with handcuffing a sloppy, confused drunk driver crosses the line into what requires a report? How about that outstretched open hand that makes contact with an aggravated domestic violence abuser to keep him away from his victim? At what point does the physical gesture become "force?" When does that hand transition from a line-in-the-sand...to a shove?

If you think that every time a police officer holds back a worried mom or her 100-pound teenage daughter on a family dispute is a UoF incident, you're frankly out of your mind! There are plenty of times a police officer touches, grabs, and re-directs people that should simply NOT be classified as a UoF incident.

But any reporting benchmark will be subjective, will rely on interpretation, and will be fraught with disagreement. Different supervisors will interpret differently whether a certain police action crossed the threshold to include as a UoF incident or not.

You might be asking yourself why should we care about these low levels of force. Sounds like we are splitting hairs with these low level grabs, pushes, holds, and escort moves. But I want to make three (3) points with this:

- Variances in this reporting benchmark can really skew UoF incident numbers. I'm talking about several types of discrepancies:

- discrepancies between different police agencies that employ different reporting benchmarks, practices, or standards -- which will make some agencies appear to have more/less based on this variance;

- discrepancies between supervisors & officers that interpret differently -- which will make some officers/teams appear to have more/less based on this variance;

- discrepancies between years -- which make agencies look to have trends, patterns, or changes that do not really exist.

- These discrepancies highlight the impossibility to quantify, measure, mechanically-apply, or accurately categorize police UoF.

- These variances matter because the vast, overwhelming majority of any police agency's UoF incidents occur at these very low, relatively insignificant levels of physical engagement.

CONTINUUM APPROACH

Step 001 is to determine what is or is not to be considered a UoF. Once a police action is determined to have crossed this arbitrary benchmark, we expect certain types of categorization of that force. As a police community, we tend to categorize "force" in the following manners, in no particular order (for a very particular reason):

- empty/open hand control

- K9 bite

- firearms

- baton

- Taser

- handcuffing / restraint equipment

- officer presence

- strikes / kicks

- take-downs

- beanbags / rubber bullets

- pepper spray / chemicals

- knives

- pressure points

- vehicles

- verbal commands

These are very broad categories...of which I'll spare you the pages and pages of commentary I could share about each.

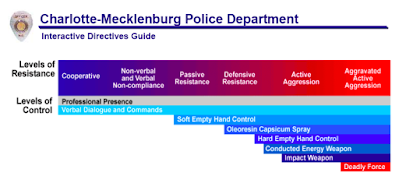

In attempts to show a spectrum of force, police agencies and organizations create one (1) or two (2)-dimensional depictions -- which also attempt to categorize suspect/subject behavior. Broader categories are also used in some models:

- non-deadly;

- less-than-lethal;

- less-lethal;

- deadly force.

(I get it -- your police agency calls it something else. Or cleaves the categories differently.)

Some of these models are no longer used by the agency depicted on the model:

This is the Continuum approach. Match an officer's response to the subject's actions, to avoid under- or over-reacting. Sounds simple enough.

However, within each category, there is a tremendous amount of variance. So much so that another approach to police UoF emerged. It's known as the Case Law approach, or the Objectively Reasonable approach.

CASE LAW APPROACH

This philosophy relies upon the standards enacted by various courts through their opinions. The overarching case is Graham v Connor (1989). (If you're not familiar with the details of this case, you probably shouldn't be in this debate.) This opinion gave police officers the Objectively Reasonable standard -- where an officer's actions would be judged against those of a "reasonable officer."

Whoever the heck that is.

- Is it the ten (10)-year veteran who dutifully attends all the required training courses?

- How about the obese officer stuffing his face with yet another greasy sandwich?

- The tactical guy (with Oakley sunglasses of course) who can keep his cool?

- The homicide detective who's putting herself through a Master's degree program?

- How about the indecisive "Hey sarge, what should I do?" guy?

- The 29-year veteran who's done so little you'll all forget him next year when he retires?

If you were to threaten me with...

- being hit in the leg with a baton;

- being punched in the face;

I'd have to ask WHO was delivering the punch and WHO was swinging the baton. Certainly it would be from real officers...not merely an imaginary "reasonable" one...

The "Objectively" part of Objectively Reasonable hits at the nature that an officer's action is either judged as reasonable or not. The line itself is a rather arbitrary, subjective one (1) based on historical arbitrary, subjective judgments ("case law"). It's basically a binary Pass-Fail test, much like Guilty-Not Guilty.

Police agencies that have UoF policies that mirror case law do so with the appreciation that their policy automatically shifts with the established, and ever-changing legal standards. It's a consistent approach that aims to harmonize state statutes, case law, and department policy. Sounds fair.

But the guidance from case law tends to....suck. It's a fair judgement standard for determining Pass-Fail in hindsight. It does a horrible job in assisting police officers to make their best decisions in real life encounters, in training scenarios, in operational pre-planning, in incident debriefs, or in tabletop discussions.

At its core, the case law standard fails to recognize the other options that might be better. It only determines whether or not what was used was reasonable. (Please re-read these statements for how I've selected past vs present tenses.) Case law is not meant to or designed to be a training aid or a practical thinking model. Case law puts bottom limits on what is acceptable. As my co-trainer and attorney Keith Karlson puts it:

Case law ensures D- grade policing.

In summary, the case law approach give us constraints or limits, as opposed to guidance for good policing.

HYBRID APPROACH

We need to build in nuance into this conversation. The complexity and uncertainty of UoF is not lost on me. Neither are the human factors. However, there are patterns and clusters that we can exploit.

First, we must understand that most any UoF tool, technique, or weapon can be applied to the "Deadly Force-degree." This is actually where I start teaching UoF:

How can each of these categorized types of force kill someone?

Basically, how can/could we kill someone with a Taser; with a rubber bullet; with our bare hands. It's a truly powerful conversation that brings out so many circumstantial, contextual, situational issues. When we examine factors that go into "death or great bodily injury," we start to identify significant variables in a UoF situation:

- distance

- power levels

- number of application

- duration of force

- technique of force

- strength/build/stamina/skill/etc of officer

- strength/build/stamina/skill/etc of subject

- targeted body areas on subject

- and a dozen more you'll tell me I've forgotten or omitted

This exercise allows us to have more meaningful conversations about how tools, techniques, or weapons were designed or intended to be used, and how variables scale them up or down in a conceptual quantum of force.

What's the conceptual unit of measurement for force? That too is complex, and if impossible, I'll argue yet still worthy of debate:

- likelihood for an injury/death?

- type of injury?

- maximum possible injury?

- statistically-probably injury?

- subjective level of violence/aggression?

- potential for unintended consequences / failure?

- awfulness of how it appears to ignorant onlookers?

- confidence/likelihood of it being effective?

Some of the categories are relatively officer-independent -- meaning that it means little who is behind the tool. This applies for things such as Taser, beanbag shotguns, and firearms. The same force is delivered from a gun fired by 100-pound shooter as by a 300-pound shooter.

But back to my question earlier: WHO was delivering the punch and WHO was swinging the baton?

Also: Who is receiving the punch or the baton strike?

It's as if our one (1)- and two (2)-dimensional depictions must be expanded to a dozen dimensions. Or more. I understand 3D (depth)...and even 4D (time)....but infinite-dimensions?.....hmm...

Every officer, not just a "reasonable" officer, can look at their own UoF options as a more complete and integrated system. It's almost as if there is a dynamic, customized, yet sloppy UoF continuum for each officer, against each subject, at each slice of time during an encounter, at different points in his/her career.

Pow! This is where some of your heads are about to explode.

- This is too subjective!

- You can't process that during a life-or-death situation!

- Case law doesn't require this!

- You're trying to mechanically-apply a model to UoF!

To which I'll respond: Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes.

This is a training tool. Maybe better described as a thinking framework. This is how we can help our officers make decisions in scenarios. How we can help debrief training, real incidents, or video case studies. How, if we maintain our inner Professor, can help process options on the street. And through training, experiences, and conditioning, if we must rely on the Caveman, gives us a better repertoire of implicit, intuitive responses.

SUMMARY

This hybrid approach still cannot quantify, measure, mechanically-apply, or accurately categorize force.

However, it does a considerably better job of comparing, overlapping, relating, tiering a variety of limitless options...all without violating any established statute, case law, or case law-derived policy.

It's almost as if there is a dynamic, customized, yet sloppy Use of Force continuum for each officer, against each subject, at each slice of time during an encounter, at different points in his/her career.

Police use of force is extremely complex and nuanced. Not helping the decision-making process is an environment where the stakes are as high as any worldly venture: life or death.

Use of Force continuums have been under attack for decades. However, there are now police reform groups calling for their resurrection. This is a mistake. We will be back to overly rigid, If-Then, one-size-fits-none approach to UoF.

Case law advocates often have a tough time providing practical decision-making guidance for their learners. The case law standard are the perimeter of a constrained box, without help on how to best behave inside the box; only whether or not you're inside or outside the box. (NOTE: I still believe that case law provides a good standard for after-the-fact determinations of reasonableness. And I support policy that mirrors case law. But training is different than policy.)

I hope you'll consider this hybrid approach. It's asking for a departure from two (2) well-established opposition camps. To form something better. To help our profession. By helping our cops.

Then maybe we can move onto discussing the infinite tactics that brought us to the encounter. Maybe.

***

Lou Hayes, Jr. is a criminal investigations & intelligence unit supervisor in a suburban Chicago police department. With a passion for training, he studies human performance & decision-making, creativity, emotional intelligence, and adaptability. Follow Lou on LinkedIn, & also the LinkedIn page for The Illinois Model.

Comments

Post a Comment