Adaptive Problem-Solving, From the Hospital Emergency Room to the SWAT Team

In December 2013, I wrote and published a blog post titled The Doctor in SWAT School (and What His Performance Says About Police Culture). Thanks to the overwhelming sharing of the post, it is one of my most visited pages on The Illinois Model website. It's a real life story with an accompanying theory in perpetual refinement.

The story begins with an emergency room physician named Jeremy (his real name). We met through my wife, an ER/trauma nurse who worked with him in Chicago. Jeremy took an interest in my job as a SWAT police officer, as he had aspirations of volunteering as medical support for a local SWAT team.

I helped Jeremy find a team willing to take on a doctor in a support role - usually in the safety of an armored truck or down the block at the command post. But Jeremy is an overachiever. Instead of enrolling in an abbreviated training class for unarmed (and limited-role) tactical medics, he weaseled his way into proverbial boot camp for veteran police officers transferring to SWAT teams. Jeremy challenged himself, knowing the skills he'd learn would be above and beyond those he'd be tasked with in real life police emergencies.

Jeremy not only survived the school; he excelled. His trainers told me he was the best performing student in the class! This shocked me - because he was a doctor among seasoned police officers.

To me, there was only one theory how this could happen. There must be something similar in the traits of a successful emergency room physician...to those desired in our police SWAT team members. The ambiguous answer lay in his decision-making abilities. But I needed something more concrete than that. What mental or emotional attributes made Jeremy excel outside his normal environment?

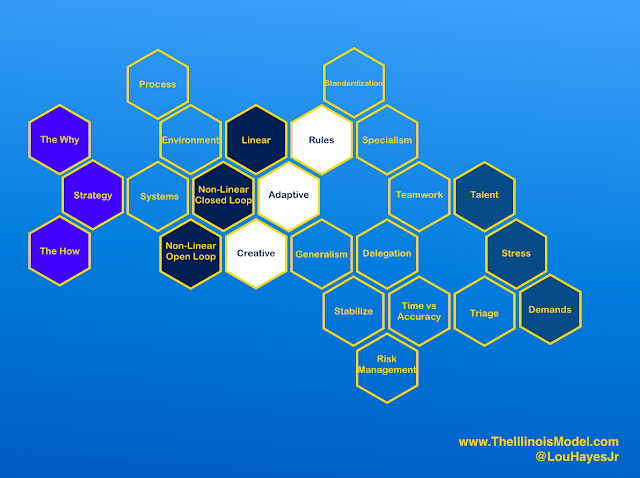

In that original The Doctor in SWAT School blog post, I detailed a list of connected theories:

- Process & systems thinking

- Non-linear decision-making

- Problem "triage" & prioritization

- Balance of a decision's accuracy & timeliness

- Implementing "stabilizing" strategies

- Acceptance of chaos & the unknown

- Delegation mindset

- Benefits of being a "generalist."

What are some other attributes that helped the doctor tackle wicked tactical police problems?

- Goal-driven. Being goal-driven is not in conflict with prioritizing "process" over "outcome." Goal-driven people keep their mind on an objective or desired end state. But they are not blinded to looking outside certain procedures or routes that have gotten them there in the past. Linear thinkers rely on step-by-step instructions, rehearsal, or tradition; non-linear thinkers move through a cycle of re-orientation like a corkscrew. It's a state of perpetual feedback and re-evaluation, all while moving forward towards satisfying the mission.

- Separating signal from noise. The digital age gives us real-time data and instantaneous feedback. But how do we filter out the important from the unimportant...or worse, the distracting? Adaptability requires that we consider what types of stimuli, change, or information are vital to our decision-making process. Each environment might use different medium to receive these signals - computer analysis, advisory boards, sensory perceptions, tolerance alerts, pattern recognition, customer surveys. A constant state of awareness allows us to adapt early and accurately.

- Risk vs Reward. I don't care if you're talking about minimizing losses...or maximizing gains. The theories of risk management are the same. Adaptive problem solvers are those who quickly synthesize futuristic "models" of what could happen as a result of each possible decision - and extrapolate those outward like branches on a tree (or boxes on a flow chart). Objective measurement is not necessary to compare alternatives.

- Prediction. With these models of the future comes forecasting. Predicting what will, should, or may happen can be (to some extent) based on algorithmic thinking. In some industries, with the right data or measurements, the confidence in the future is high. In open-loop environments, or where objective data or metrics are unavailable, the confidence can be miserably low. For those who know Colonel Boyd's OODA Loop, thinking ahead is a sort of "pre-orienting."

- Shape the Environment. Once an adaptive problem-solver understands how risk or reward are weighed, or how forecasting helps predict the future, s/he should mold the circumstances so that as many potential problems can be eliminated as possible. Similarly, s/he should "stack the deck" to keep as many doors open to positive outcomes or successes. Shaping the environment is about building off small, seemingly inconsequential decisions, until they collectively add up to a decisive advantage.

- Know when to go "all-in." In no-limit poker games, players are allowed to make bets as large as their entire stack of chips. If a player does this and loses, the player must leave the game, as s/he no longer has any money left to wager. Going "all-in" is a decision that cannot be made lightly. But at the other extreme is a vacillation. Adaptive problem solvers maximize opportunities and alternatives...until that moment where nothing but absolute resolve, commitment, and decision is necessary.

Jeremy spent several years as a physician for a Chicago area SWAT team's tactical medical unit. He figured out how to transfer these soft skills from his experiences as an ER doctor into a fresh landscape of law enforcement emergency response. And from my conversations with him over the years, this is not something that Jeremy turns ON or OFF just while he's in the emergency room attending to sick or injured patients. This is simply how he lives and makes decisions for everything in his life. It's who he is.

So maybe the next questions should be whether or not these traits can be taught, learned, or grown in humans? Is it a product of experience? Workplace culture? Growth mindset? Problem-solving games? Case studies? Paranoia? Focus?

I've yet to hear anyone argue against adaptive problem-solving. Most appreciate the theories of adaptability, agility, or flexibility as necessary attributes to success in chaotic or stressful situations.

Are we doing enough to articulate or codify what adaptability is all about?

If not, how do we expect to replicate it?

***

Lou Hayes, Jr. is a police training unit supervisor in suburban Chicago. He studies human performance & decision-making, creativity, emotional intelligence, and adaptability. Follow Lou on Twitter at @LouHayesJr.

Comments

Post a Comment